I am a humanist. I do not believe in an afterlife but (to quote Woody), “Just in case, I’m bringing a change of underwear.”

I don’t deny or affirm the existence of God, any god. There have been so many, and all of them had their vague charms and serious hang-ups, ranging from the violent to the sexually perverse. Who could know which to worship? No one. That’s why we usually end up with the god our grandfathers worshiped.

Whether there is a God or not is simply of no consequence to me, and if the truth be told, can anyone in raw honesty claim that the God they pray to for answers, solutions, reversal of fortune, pie-in-the-sky or redress of grievances ever–ever answers their calls. Of course not. I can still see the pious face of a too-close relative asking me, as my mother lay dying in a hospital ICU, whether I believed God answered prayer. “It depends,” I said. “What are we praying for?”

I am an Unbeliever, of sorts. Joylessly so. I have no axe to swing at the necks of believers. I dislike the word “agnostic.” It sounds as precious in tone and as pretentious as the era when it was coined. It sounds as though we wait patiently for some impossible verdict to emerge from the skies confirming our hunch that we were right to disbelieve all along, Descartes and Pascal be fucked. But it’s not really about evidence, is it? It’s about hunches.

I am not an atheist. But it is a noble thing to be, done for the right reasons.

There are plenty of good reasons to be an atheist–most of them originating in our human disappointment that the world is not better than it is, and that, for there to be a God, he needs to be better than he seems. Or, at least less adept at hiding his perfection.

But you see the problem with that. Goodness and imperfection are terms we provide for a world we can see and a God we don’t. Taken as it is, the world is the world. Taken as he may be, God can be anything at all. I’m not surprised by the fact, human and resourceful as we are, that religion has stepped in as our primitive instrument, in all its imaginative and creative power, to fill in the vast blank canvas that gives us the nature (and picture) of God.

But let’s be clear that God and religion are two different things, and that atheists err when they say “Religion gave us God.” What religion gave us is an implausible image of God taken from a naive and indefensible view of nature. I find my atheist friends, even the “famous” ones, making this categorical error all the time.

There are also some very silly reasons to be an atheist. The silliest is the belief that the world wasn’t made by God because God doesn’t exist and that people who think this are stupid and ignorant of science. There are so many fallacies packed into that premise that it’s a bit hard to know where to begin picking. But perhaps this analogy will help: This clock wasn’t made by Mr Jones because I made Mr Jones up in my head. It was actually made by a clockmaker whose name is lost in the rubbish of history, so if you continue to think Mr Jones made it just because I said so, you’re ignorant.

No, that is not a broadside in favor of intelligent design (though I happen to think the atheist approach to the question is often tremulously visceral); it’s a statement about how we form premises. The existence of a created order–a universe–will ultimately and always come down to a choice between the infinity of chance and the economy of causation, but in any event, my causation is not muscled and bearded and biblical. That much we can know

I am a realist. I believe (with a fair number of thinkers, ancient and modern) that human nature is fundamentally about intelligence and that the world (by which I really mean human civilization) would be much further on if we stopped abusing it. I regret to say, religion has not been the best use of our intelligence, and it has proven remarkably puissant in retarding it. Science is always to be preferred, except in its applied, for-profit form (as in weapons research) because it expands our vision and understanding of the world while religion beckons us, however poetically, to a constricted view of cosmic and human origins.

To be a realist makes me something of a pessimist (a term going out of fashion) not because I don’t believe in the capacity of human nature to become what it seems designed to be, but because–realistically–we have become as flabby in our thinking as we have become corpulent of mortal coil. Being a realist means we can’t do or know everything–with a tip of the hat to my scientifically progressive friends whose promethean visions I find engendered with a kind of cultic spirituality that makes me squirm. Science after all, like religion, was created by us. One of our tasks is to learn and teach its secrets and take it away from the priestly caste it has created.

When I hear the chorus of scientific naturalists moaning that hoi polloi are dim, that the secret to intellectual salvation comes through a door locked by secrecy and formulas the laity are unable to cipher, I’m always reminded of the ancient hierophants who guarded their own secrets closely and made sure they were passed down only through a priestly elite. And even though I know–theoretically–that science does not encourage secrecy in that sense and is–theoretically–democratic in its outreach, in practice it has been very bad in wholly communicating and exegeting its mysteries beyond the gates of MIT and Caltech. In other words, is it only religion we must blame for the scientific illiteracy of the masses?

But in the end, I am a humanist. Humanism incorporates the rest of it, the unbelieving, the realistic, the pessimistically hopeful. It also includes the aesthetic, and this can be something of a dilemma at this time of year–which, by the way, I am happy to call Christmas and not “the Holiday season” or “Winterfest” or “Solstice.” Winter is not to be feted but avoided. Saturnalia (the Roman Solstice holiday celebrated on December 17th) was just like its replacement, Christmas, a religious holiday in honor of the birth of a god, though a lot more fun.

And I have a weak spot. I love religious music, especially at this time of year. Bach and Handel spun the most amazing cantatas and oratorios out of the Christian myth. They are irreplaceably wonderful. Beyond that, the sheer melodic simplicity of “Silent Night” (perhaps the best song ever written) and the shivering loneliness of “In the Bleak Midwinter” stir the poet in any human soul. “Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone.” Think of that the next time you’re shoveling out.

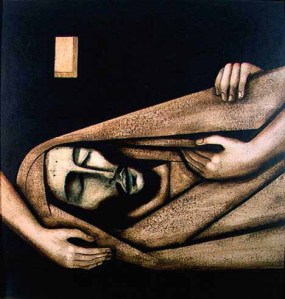

I don’t believe that Jesus, if there was one, was born in a manger, but I think the idea of pure, naked, vulnerable–even unwelcome–humanity as expressed in religious nativity art and poetry is humbling and moving. And I think the end of the same story, as an allegory of our humanity, naked and vulnerable at the end, is not a contradiction of dignity but an acknowledgment of mortality.

It is something we will all have to do eventually–face our end, I mean. For the humanist that confrontation underscores our belief that a human life is what we’ve got to work with. That we do not seek our rewards, satisfactions or compensation in some unplotted and mythical kingdom.

It is an intelligent, humanistically compelling thing (as philosophers used to remind us), to see the art of dying as the other side of the art of living well. Humanists need constantly to remind themselves that non-belief is not the same as living well or facing death courageously. I think, personally, that mangers and crosses are as relevant to my humanity as the visions of Apollo and the pleasures of Dionysus. Use the myths wisely, but use the myths.